Your Computer Is Not Secure

Your Computer Is Not Secure

A man in a Connecticut prison found that out the hard way: he says the FBI convinced Hewlett-Packard to let them into his hard drive through a secret doorway.

By Meir Rinde

When agents from the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms arrested convicted felon Michael Crooker on a charge of illegally shipping a firearm across state lines, they searched his apartment in the Feeding Hills neighborhood of Agawam, Mass. and found substances that gave them pause.

They called in military and civilian hazardous material units, and a bomb squad, and police closed off all areas within 1,000 feet. A story spread that investigators found the poison ricin in the apartment; in reality, they found castor beans, which have commercial uses but do contain ricin.

They also found lye, which is used in ricin production, and rosary peas, which contain a toxin called abrin. In Crooker's car they found powerful homemade fireworks, and they conducted a controlled explosion of at least one device.

That was almost two years ago. He's now locked up at the state correctional facility in Suffield Connecticut, awaiting trial on a single charge of trying to ship an air-gun silencer to a man in Ohio.

The 52-year-old ex-con fills his time studying his case and writing letters to the judge, as well as filing lawsuits against the government and other parties, as he has done all his life.

Among the entities he has targeted is the computer maker Hewlett Packard. In his suit, Crooker traces back the history of his Compaq Presario notebook computer, which the ATF seized when he was arrested.

He bought it in September 2002, expressly because it had a feature called DriveLock, which freezes up the hard drive if you don't have the proper password.

The computer's manual claims that "if one were to lose his Master Password and his User Password, then the hard drive is useless and the data cannot be resurrected even by Compaq's headquarters staff," Crooker wrote in the suit.

Crooker has a copy of an ATF search warrant for files on the computer, which includes a handwritten notation: "Computer lock not able to be broken/disabled. Computer forwarded to FBI lab." Crooker says he refused to give investigators the password, and was told the computer would be broken into "through a backdoor provided by Compaq," which is now part of HP.

It's unclear what was done with the laptop, but Crooker says a subsequent search warrant for his e-mail account, issued in January 2005, showed investigators had somehow gained access to his 40 gigabyte hard drive. The FBI had broken through DriveLock and accessed his e-mails (both deleted and not) as well as lists of websites he'd visited and other information. The only files they couldn't read were ones he'd encrypted using Wexcrypt, a software program freely available on the Internet.

Despite the exposure of his e-mails, Crooker isn't in prison on a chemicals or explosives charge. Rather, he's been detained for two years on a single firearms charge because the judge thinks he's too dangerous to let out on bail.

A six-page rap sheet included in his firearms charge file lists arrests going back to March 1970, when he was 16 and committed an armed robbery while wearing a ski mask, according to the Springfield Republican. In 1977, he was accused of threatening to kill President Gerald Ford; he was cleared, but convicted of mailing death threats to the police chief of Southwick, Mass., where he grew up, and to a probation officer.

In 1986, he was charged with rape and attempted murder; the charges stemmed from a phone argument with his wife, he says, and were dropped. In 1993, he plead guilty to a conspiracy to possess guns, witness tampering -- he admits he blew up a witness's car -- and IRS fraud. He and an accomplice had filed about 70 false tax returns and pocketed the refunds.

The judge who ordered him to remain incarcerated described Crooker as "a real threat to the community at large, if not particular individuals as well." The judge wrote that prosecutors believe Crooker has made ricin in the past; that he is accused of keeping three hundred rounds of ammunition at his parents' house; that in letters he refers to Timothy McVeigh as a "martyr" and "expresses admiration for Osama bin Laden's brilliance."

If the government agrees Crooker is so dangerous he can't stay at home while he awaits trial, should he be allowed to use purportedly unbreakable computer security systems to hide potentially criminal activity?

Because of cases like Crooker's, some might argue the government should have access to security backdoors to discourage criminals or at least catch them more easily, much as the technology in the movie Minority Report allows police to prevent crime by arresting criminals before they act.

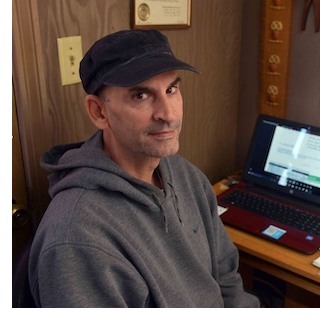

Of course, Crooker does not agree. Sitting in a low-ceilinged prison visiting room last week, his bright yellow prison jumpsuit hanging loosely on his narrow six-foot frame, Crooker rifled through stacks of legal documents and criticized what he described as HP's deception in not admitting up front that DriveLock was flawed, and in selling him out to the feds.

"Even if it's the CIA and the NSA, it's wrong for HP to say, "we can't help you if you lose your password'," he said. "It's causing people to hide things on their computers, and they're not secure."

Crooker argues that by providing the FBI with a way to circumvent DriveLock, and claiming the system was impenetrable when there was actually a backdoor, HP committed a breach of contract.

We left a message for HP's lawyer, Thomas W. Evans of Cohen & Fierman in Boston, and got a call back from Ryan Donovan, a company spokesman in Palo Alto, Calif.

"We don't comment on pending litigation," he said.

In a legal response sent to Crooker but not yet available in court, Evans says HP didn't help the FBI, and argues it was unreasonable for Crooker to expect that data he entered on the laptop would remain inaccessible to others.

Crooker's goal is primarily to get money from HP. He's demanded $350,000, and would probably accept much less. But he has also stepped into a much larger debate over computer security: whether HP and other companies are providing their customers with sufficiently strong protection and whether the government should allow anyone access to security systems so strong that even federal law enforcement agents have a hard time breaking through them.

Crooker has spent many years in prison, but he's had some success with the law as well. In 1984, when he faced a charge of having an unregistered machine gun, a federal District Court panel reviewed his claims that he should have access to certain ATF documents. Although he ultimately didn't get everything he wanted, the judges ruled ATF hadn't given a specific enough reason for withholding the documents, and Crooker v. BATF became an important footnote to discussions of Freedom of Information law.

In his current criminal case, he argues that although the silencer would fit on an actual firearm, it was only intended for use on the air gun it was attached to. "You wouldn't believe the hearings and motions we've filed on this," he said.

He knows firearms law inside and out. He's published a pamphlet called A Felon's Guide to Legal Firearms Ownership, which you can buy online for $4.95.

But his lawsuit against HP may be a long shot. Crooker appears to face strong counterarguments to his claim that HP is guilty of breach of contract, especially if the FBI made the company provide a backdoor.

"If they had a warrant, then I don't see how his case has any merit at all," said Steven Certilman, a Stamford attorney who heads the Technology Law section of the Connecticut Bar Association. "Whatever means they used, if it's covered by the warrant, it's legitimate."

If HP claimed DriveLock was unbreakable when the company knew it was not, that might be a kind of false advertising.

But while documents on HP's web site do claim that without the correct passwords, a DriveLock'ed hard drive is "permanently unusable," such warnings may not constitute actual legal guarantees.

According to Certilman and other computer security experts, hardware and software makers are careful not to make themselves liable for the performance of their products.

"I haven't heard of manufacturers, at least for the consumer market, making a promise of computer security. Usually you buy naked hardware and you're on your own," Certilman said. In general, computer warrantees are "limited only to replacement and repair of the component, and not to incidental consequential damages such as the exposure of the underlying data to snooping third parties," he said. "So I would be quite surprised if there were a gaping hole in their warranty that would allow that kind of claim."

That point meets with agreement from the noted computer security skeptic Bruce Schneier, the chief technology officer at Counterpane Internet Security in Mountain View, Calif.

"I mean, the computer industry promises nothing," he said last week. "Did you ever read a shrink-wrapped license agreement? You should read one. It basically says, if this product deliberately kills your children, and we knew it would, and we decided not to tell you because it might harm sales, we're not liable. I mean, it says stuff like that. They're absurd documents. You have no rights."

Schneier entered the field of computer security as a cryptographer. He invented an algorithm called Blowfish, which is used in many software programs including Wexcrypt, which Crooker used on some of his files, and which the FBI has apparently been unable to crack.

In recent years Schneier has been a prominent critic of most computer security schemes, saying that they're not reliable in part because companies aren't financially liable for failures. He described Crooker's lawsuit as "kind of funny."

"Part of me says, 'Well, go get them,'" Schneier said. "Because the industry, for years, makes all of these false promises. So here's someone who's saying, 'Look, goddammit, I believed them, and I got arrested,' or something. So that's kind of neat, actually."

Online, self-declared computer geeks have discussed at length how to unlock DriveLock'ed hard drives. The general consensus is that, unlike many computer password systems, DriveLock is a hard-drive-only system, a technology added to the drive, rather than a routine in the computer software. Only a chip on the hard drive knows where the password is stored, and the chip simply will not allow the drive to spin if the password is not provided. Putting the drive in a different computer, or tinkering with computer system files, doesn't help. Encryption isn't the problem, either: your files may just be sitting there, in readable form, but the drive refuses to work.

The computer geeks seem to throw up their hands at devising a home-office method of getting around DriveLock. However, in a "clean room" laboratory setting it should be possible to take apart a hard drive and scan the platters where magnetic information is stored.

A few companies advertise password removal services for a fee, such as Nortek Computers Limited, in North Bay, Ontario, Canada. For $85, the company will simply erase your hard drive, which removes the password and at least makes the drive useable again. For $285, the company will copy your information off the drive, wipe the drive, and put the information back on, sans the password, said Chris Boyer, a support specialist at Nortek.

He wouldn't describe how it's done, except to say that some computer drives can be penetrated using "non-invasive" methods, while others are more difficult. "There's quite a bit involved, engineering-wise and facility-wise," Boyer said. The company is alert to suspicious clients who seem to be trying to break into someone else's computer, and keeps records of device serial numbers, he said. It has removed passwords for law enforcement agencies in the U.S., Canada, England, Denmark and other countries.

The availability of commercial password removal suggests HP may be sincere when it says it didn't help the FBI. But Crooker said that's no obstacle to his lawsuit. "Why are HP and Compaq still advertising this DriveLock system when they have to know about the Canadian operation for $285?" he asked. "They're lulling us into this sense of security, when for $285 it can be exposed? It ain't right."

In the recent past the federal government has attempted to build in backdoors to certain computer systems: In the early 1990s, the National Security Agency tried to require the installation of a chip in phone transmission systems, so agents could eavesdrop on encrypted conversations. The Electronic Frontier Foundation and other civil liberties groups attacked the proposal, which eventually died (although recently AT&T reportedly allowed the NSA to monitor millions of phone calls without warrants, using specially installed supercomputers).

So while DriveLock may not be wholly secure, software that uses Blowfish and other encryption methods remains widely available. To civil liberty advocates, that's good news, even if it means individuals like Michael Crooker can hide their secrets from law enforcement.

"Encryption software is becoming a very ordinary thing. That's a very positive development in terms of limiting the erosion of privacy in certain ways," said Seth Schoen, a staff technologist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Crooker said he understands the argument for allowing the government to penetrate computer security systems. "I can see both sides of it," he said. But that doesn't mean he's letting HP off the hook for pretending DriveLock was really secure."

That's a point security experts would agree with: undisclosed flaws are the Achilles' heel of any security scheme, because then the user of the system doesn't even know what kind of incursions to watch out for.

For Bruce Schneier, the key to preventing such flaws is the kind of legal liability that Michael Crooker is trying to create, forcing companies to pay though the nose until they develop security that really works.

"Unfortunately, this probably isn't a great case," Schneier said. "Here's a man who's not going to get much sympathy. You want a defendant who bought the Compaq computer, and then, you know, his competitor, or a rogue employee, or someone who broke into his office, got the data. That's a much more sympathetic defendant."

Copyright 2006, 2007, New Mass Media. All Rights Reserved.